Why Sports Records Will Continue To Be Broken

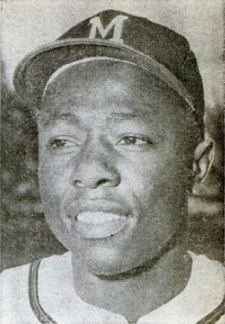

Hank Aaron took the home run record from Babe Ruth, and lost it 33 years later to Barry Bonds. (Public domain photo)

At this writing, the 2011 Women’s World Cup of Soccer/Football (take your pick) is in full swing. As a gringo I’ve been following the US team, and have had many earfulls of the comparisons between Abby Wambach and former US player Michelle Akers. Akers was renowned for drive and toughness, nearly always playing with some injury wrapped or taped, and never slowing down. She had little need to throw the dramatic fake injury performances common on so many of the teams. And now we see the monstrously powerful Abby Wambach playing with much the same gusto. She’s been called “the next Michelle Akers.”

And this happens in all sports. Formula 1 racing had Fangio, Clark, Senna, then the all-conquering Schumacher whose records were so many and so untouchable that it seemed they’d never fall. And guess what; fans are already saying “Schumacher who?” as they watch the young Sebastian Vettel tearing up through the ranks.

Baseball greats are many; new records come pretty regularly. And just look at any Olympic games: World records are set every year in many sports. Names like Mark Spitz and Johann Olav Koss, once untouchables, have become footnotes. Why is this? Why do even the loftiest of sports records continue to fall?

We often point to improved training, better technology, better conditioning. Knowledge of how the sport should be played accumulates, and newcomers get to stand on the shoulders of giants. There are better ice skates, better swimsuits, better bicycles. There are lots of reasons we should expect performance to improve overall.

But even without that, there is a simple fact of statistics which guarantees that records will continue to be broken, even if you take all of the technology and improvements out of the equation. With all else being equal, a greater total number of participants in a sport, throughout its entire history, will produce a greater number of top players and better performances. Every year the total number of historical participants grows, so every year the likelihood of a record-setting performance increases.

Let’s say that 100 new people enter the sport of long jumping every year. Assume that by 1950, 1,000 athletes had participated in the long jump at some point. Fifty years later, by the year 2000, 6,000 athletes had participated (100 per year × 50 years + the original 1,000). The performances of those first 1,000 form a bell curve. Even with no advances in sports technology or knowledge, the performances of the 6,000 form a curve of the same shape, but six times higher. There are six times as many average performances, six times as many really bad performances at the low end of the tail, and six times as many extraordinary performances at the high end of the tail. Over time, it’s more probable that the best record-setting performance will be found within the larger bell curve than within the smaller.

Even if only one new athlete enters a sport in any given year, it’s more probable that the best-ever performance will be found in that year’s sum total of all performances than in the previous year’s slightly smaller sum total. Even a sport on the decline is likely to see new records.

So don’t expect the smashing of sports records to stop, either anytime soon, or ever. Athletes need not become superhuman, they need not find better technology or better training, they need no cybernetic implants or super high tech exercise machines. They need only their own ever-growing numbers.

And as Abby Wambach knows, Marta is already on the soccer fields…

By what reasoning do you assume that the performances of long jumpers follow a bell curve? First of all, it can’t be a bell curve, as there is a clear minimum. Bor more importantly, do you really think there is a small, but finite chance that some day someone would jump 10 meters? Or 100 meters? There is a physical limit to the amount of energy a human body can produce, and utimately, that’s going to limit the distance a human can jump. That limit means that the distribution of long jump performance can’t be a bell curve.

It doesn’t matter what the upper and lower limits are, the data will still fit a bell curve. There is no implication for what the upper or lowers limits of the curve will be, and it certainly does not require an infinitely long x-axis.

I think there are several records in baseball that will never be broken, mainly because how pitchers are used has changed drastically in the last 100 years. Take these Cy Young records for instance:

511 wins (Greg Maddux is the only modern pitcher close and he struggled to get to 355 wins)

7356 innings pitched (Nolan Ryan had to play 27 seasons to get to 5386)

815 games started (Ryan came close at 773 but would have needed another 2 season to get to 815)

749 complete games (absolutely untouchable the way relief pitchers are currently used)

7092 hits given up (Phil Neikro pitched until he was 48 and only got to 5000)

316 losses (Ryan came close with 292)

I’m not saying Cy Young was the greatest pitcher ever but he played in a very different era where pitchers could accumulate ridiculous stats by pitching every other day. The way the game is played now someone would have to pitch until they were in their 50s to get close to most of those stats. Not inconceivable but very unlikely.

Another baseball record that is unlikely to be broken is Joe DiMaggio’s 56 game hitting streak in the summer of 1941. There have been, and will be baseball hitters whose skills match or surpass those of DiMaggio, but changes in pitching and the way that pitchers are managed have changed. In Joe’s day, pitchers often ‘went the distance” pitching a full nine innings. So Joe got to see the pitcher’s stuff and adjust to his timing four or five times in a game. As every manager knows, a team’s batting average goes up the second time through the order against the same pitcher, and by the fourth time through a tired pitcher will have little left to show a skilled batter. So, now, the starting pitcher is usually pulled in the sixth or seventh inning after about 100 pitches and the batters have to adjust to a whole new set of pitches, velocities, and rhythms. In the ninth, if our hero hasn’t already extended his streak, he’s confronted with a specialist “closer” whose ERA and opposing batting averages are both below .200. I doubt the DiMaggio could have run his magnificent string against that pitching strategy. Add to that the rise in the use of the slider since the 1950’s, it is unlikely that DiMaggio’s record will ever be broken unless the rules of baseball or baseball equipment change to greatly favor hitters.

Using your example, in 1950 the record would be broken if any of 100 participating athletes was better than 1000 preceding athletes, but in 2000 the record would be broken if any of 100 participating athletes was better than 6000 preceding athletes. The number of participating athletes in a given year stays the same, but the number of athletes they have to beat keeps growing, so it takes longer and longer to break the record.

This rather supposes that the factors that effect performance are otherwise static. Clearly things can improve, such as training, diet, performance enhancing drugs etc. But things can also decline, such as drug doping tests, changes in tactics etc.

For example, it seems unlikely that Don Bradman’s batting record or SF Barnes’ bowling record in cricket will ever be approached by anyone else. This is in part because the tactical side of cricket has changed in the meantime.

I wonder if the mean is increasing because of technology improvements. Anyway, it definitely isn’t surprising that the highest outliers always increase. It’s a monotonically non-decreasing function.

Another example of some records that will likely never be broken: Gretzky’s goal/point records both for a single season, as well as all-time records.

This really has little to do with how awesome Gretzky was as an individual, and more to do with both how the NHL at the time allowed the team to be stacked with complimentary players, as well as the pacing, penalization, and general play-style of the game. Unfortunately (or fortunately, depending how you look at it), hockey is a much faster game now that is played with a significant eye towards zone defense, incredibly talented goaltenders who play a style that allows for maximal coverage of the net, and teams that are balanced both in talent by salary caps and salary basements that the NHL has taken a hand in equalizing poorer performing markets with better performing ones.

That said, I think there are a ton of other records that are broken every year in the NHL. I’m sure there are equivalent records in many other sports that simply won’t be broken because the rules, style, or many other factors have changed to simply not allow for it.

Great article though, and it does come right down to statistics when you think about it… never thought about it that way until now!

Assuming that the probability distribution is finite, we get something like Zeno’s paradox, where the upper limit is reached asymptotically in ever smaller increments: meters, then centimeters, then millimeters, and so on. If we plot the records over time, we may even see where the asymptote is.

Absolute records of individual performance will probably continue to fall, albeit asymptotically as someone above already said. But many sports records depend on relative performance vs. competitors and these (barring structural changes in the sport) are less generally liable to improve over time. For the classic case, see Stephen J. Gould’s essay on the demise of the .400 hitter.

Some career statistics are outstanding in a way that it is very unlikely that anyone will ever surpass them.

I am confident that the stature of Babe Ruth will never be approached by any baseball player. Remember that the Babe didn’t start setting his remarkable hitting statistics until he had already won ninety games as a star pitcher (he would later win several more), and set several records that took many years to break. His record of consecutive scoreless World Series innings pitched was broken by Whitey Ford the same year that Roger Maris had 61 homers, but like Maris, it took Whitey more games to do it. Ruth only pitched three games in two Series. It was inevitable that his career and single-season home run records would eventually be broken, and they were after some 35 to 40 years, but remember that in 1927, his 60 homers was more than the total of any other team except his own (The most any team other than the Yankees had that year was 47; Ruth’s teammate Lou Gehrig had 48 that same season.). I don’t think anyone now alive will see that accomplishment matched; it would take well over one hundred. Three quarters of a century after he retired, he still ranks in the top five or top ten for many career stats. At the time of his death he held some fifty-four records, some of which are still unmatched. I suspect that that is a record in itself, one which may also go unmatched.

Ruth’s career, taken all in all, must really stretch the upper end of that bell curve mercilessly.

Thanks for a great post Brian and for all the great comments (especially the one pointing out how we will continue to measure in smaller and smaller increments). I think a few people missed the point of the article. The idea seems to be that we often attribute records being broken for only a few reasons and often overlook the pure statistics factor.

As some have pointed our certain games have changed so dramatically so that the records will likely never be broken but I think that’s hardly the point. The fact that techniques training and equipment also likely help to some degree is also not the point. The point seems to be that there is a purely scientific and mathematical reasons why records would fall continually that seems to have been overlooked. Granted, in the real world pure math and science is influenced by unaccounted for variables.

There’s several other ways this article is wrong:

1. It ignores the fact that better training, diet, etc., ARE factors in many cases.

2. At the same time, it ignores that greater participant pools will have greater defensive competitors to tamp down on records, too. In other words, for every running back wanting to rush for 2,500 yards, there’s a linebacker bigger and faster than ever.

3. It also ignores that the greater size pool is offset by the greater number of past competitors, meaning more records to overcome.

3A. Max, with his Zeno’s Paradox comment, is on a vaguely similar line.

4. It also ignores changing conditions in many sports (DH, maple bats, changing/diminishing ballpark sizes in baseball, astroturf in many sports, shoe quality in basketball) etc. make the talk of “records” somewhat relative. Places like baseballreference.com “park equalize” as well as “era equalize” statistics. Golf is an even better example. Due to technology, the PGA has had to impose limits on equipment.

So, sorry, basically, there’s little to take away from this blog post.

1. Reread paragraph 4

2. Reread the whole post. Defensive records will continue to be broken as well.

3. Then by that argument, record breaking would begin to become an increasingly rarer event once a sport has been established for x number of decades. Generally, that’s not the case. Again, reread the whole article.

3A. whether the record is beat by a meter or a centimeter, the record is still broken. Perhaps at some point the gains will diminish to the point where some types of record breaking begin to become exceedingly rare. In general, that’s not the case now as we continue to see seemingly untouchable records broken (again, reread the entire post).

4. Valid point in general about the whole issue of records in sports (and I’d rather Brian not have used Bonds breaking Aaron’s record as an example of a record breaker for this post), but the point on this aspect of statistics is still made and is an interesting one.

So, sorry, basically, there’s little to take away from your comment (other than the fact that your emotions about Brian seem to impede your ability to think critically about his content).

It’s interesting that Brian mentions the long jump.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Long_jump#Records

“The long jump is notable for two of the longest-standing world records in any track and field event.”

In this graph, you can see the gaps between 1935 and 1960, 1968 and 1991, as well as 1991 to present.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:LongJumpProgression.gif

And 6 out of 7 records between 1960 and 1964 were set by Ralph Boston.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Long_jump_world_record_progression

1. I read graf 4 the first time. I inferred that Dunning didn’t think they were that important of a deal. If he did, he wouldn’t have written this long of a blog post.

2. In many cases, defense either doesn’t have records to be broken, they’re team records, they’re more obscure records, or all of the above. What baseball team has the best team fielding percentage in history? What football team has the best mark for fewest yards allowed per rush?

Also note JackD’s comment at 7

3. It’s arguable back that we have too small a sample size by time to argue this one way or the other, at best, in many “modern” sports. Also, I’ve read a book recently, published by ESPN, “The Perfection Point: Sport Science Predicts the Fastest Man, the Highest Jump, and the Limits of Athletic Performance,” which actually has some sports science studies on just how far records are likely to be advanced, and the limitations of human physiology.

Here’s your Amazon link: http://www.amazon.com/Perfection-Point-Predicts-Athletic-Performance/dp/0061845450/ref=sr_1_2?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1310702782&sr=1-2

3A. Many “seemingly unbreakable” records still are. Read other commenters besides Max and I; read both of Max’s comments above, as well as his response to you below. Also note that Dunning used “smashing” of records, not “slightly besting of” records. See, I read more carefully, and find more ammo!

4. But, Brian DID use Bonds. Nuff said.

It’s interesting that you assume to think my animus for Dunning’s pseudoskeptical libertarianism has somehow “blinded me,” and that you track my commenting on Dunning posts enough to make that assertion. Or, it’s “interesting.” It’s also interesting that you chose to focus on me; Max is also known for regularly commenting contrarily on Dunning posts too.

So, there’s little to take away from your comment other than you might be a Dunning-iac, or even a sock puppet! Get back to me when Dunning actually has some research, similar to the ESPN book, to report.

Oh, and if you picked up on my initial comments based on my Google-Plus post and you “following” Dunning there, sweet! That’s exactly what I wanted.

Read how Max manages to make his points on this post without unnecessary insults. Then reread your own responses.

You figure it out.

I had no unnecessary insults here. Look at my original post. I started with:

Stated the reasons why (as I wasn’t the first to object to parts of the post, the “other ways” is perfectly legit.

Then, I ended with:

In between, I never even mentioned Dunning by name.

So, nope, you’re axe-grinding, a Dunning-iac, or worse yet.

Stop bothering me until you can make a substantiated claim.

I had no insults at all, in fact; meant to state that in my original response to Scott’s unprovable claim, but forgot.

The choices you make in your writing makes it clear that you have issues beyond the content of Brian’s post(s).

For example, you felt the need to include that final sentence in your original comment. Why is that? Why not just leave it off? Max makes his points clearly and leaves it at that. You seem incapable of doing the same when it comes to Brian Dunning and Michael Shermer, and one wonders if you only read their posts to find someway to attack it, rather than calmly evaluate what points are valid and which are not. This detracts from your arguments and makes you come across as petty and immature. It makes people less likely to click on your name and see what you have to say on your own blog.

That’s how I read it. You can consider there MIGHT be a point in something I’m saying, or choose to ignore it.

But I’m sure you’ll do the former, as only ‘pseudo-skeptics’ are those who never turn their critical thinking inward.

Talk to you again on Brian’s next posting here. :)

Scott … you’ve obviously not read things Max has said on other Dunning posts, or that others have said on other Dunning or Shermer posts.

I don’t know why you seem to “have it in” for me, other than perhaps my earlier guess about Google-Plus being right.

You also assume I don’t “calmly read posts,” etc. In short, I’d say you’re also making either further non-evidence-based claims, or else “projecting.”

I’ll gladly choose to ignore you further here. And on future Dunning posts, along with your false “smiley.” .!.

One last comment to Scott. As *proof* it’s not about me, I invite you to this comment by Max on Dunning’s “gluten” post, made before I made a single comment there.

I say the same to all others who think this is a “me vs. Dunning” cage match. (And, based on Brian’s responses to Max, he knows that too.)

And, should any of you continue to make this claim, I’ll continue to reference Max’s comment.

https://skepticblog.org/2011/07/21/gluten-redux/#comment-59212

It’s interesting that Brian mentions the long jump.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Long_jump#Records

“The long jump is notable for two of the longest-standing world records in any track and field event.”

In this graph, you can see the gaps between 1935 and 1960, 1968 and 1991, as well as 1991 to present.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:LongJumpProgression.gif

And 6 out of 7 records between 1960 and 1964 were set by Ralph Boston.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Long_jump_world_record_progression

“Every year the total number of historical participants grows, so every year the likelihood of a record-setting performance increases.”

I’m pretty sure this is incorrect. Just because there is a bigger pool of people does not necessarily mean that the new participants in the pool are going to be the outliers (ie produce the record-breaking results).

Take the extreme case. If there is only one new participant in a given year, they are not more likely to become a record-holder just because 1000 people have participated before them and they are making the total 1001 (all else being equal). Yes, having a bigger n-value for the statistics increases the chance of an outlier performance. However, it does not mean that extreme outlier performance is more likely to occur this year than in the first year of the data set, or any other year for that matter.

You are correct, and if you read more carefully you’ll see that we’re saying exactly the same thing. :-)

I’m curious, at the least, about one comment by Brian early on:

First, what does race have to do with watching soccer or not? Second, if Dunning means nationality by that, the Women’s World Cup is being played in Germany, not Mexico. WTF?

It was clearly a joke. And ‘Gringo’ isn’t something just from Mexico, it is from any country that speaks Spanish or Portuguese.

Elevator Pitch

It’s time for a remake of Star Trek II, The Wrath of Khan.

Proposed Cast:

Captain Kirk: Brian Dunning

Khan: SocraticGadfly

Let’s get this done, people!

:)

Socratic Gadfly: ‘”From hell’s heart, I stab at thee. For hate’s sake, I spit my last breath at thee.”

Dunning: GAAAAADFLYYYYYY! GAAAAAADFLYYYYYYY!

He does provide a reliable source of entertainment. Sometimes I think I should start putting deliberate Gadfly bait in my posts, but then I suspect he’s actually Shirley Ghostman punking me again. :-)

You don’t really need any bait. It is YOU that he is attracted to, not the content of your posts.

If that is the best that you can do, then I don’t think Brian would even have to try to outsnark you.

I’m pretty sure you do not really understand the math behind the scenarios you are advocating here.

“Over time, it’s more probable that the best record-setting performance will be found within the larger bell curve than within the smaller.”

It’s not only more probable, it’s mandatory, since the larger bell curve encompasses all data points in the smaller bell curve and some more.

But the record breaking data point is the one located in the larger bell curve and NOT in the smaller previous bell curve, and as the small bell curve gets larger and larger, the next step in the larger bell curve is just a tiny increment of the previous smaller bell curve, so the time interval between each record setting will tend to increase further and further. Your reasoning would only hold up if you re-run the ENTIRE set of data_points for the new accumulated bell curve sample size again, which is absurd.

I was not entirely sure these remarks where true, so I’ve made a quick script in python to test that out (isn’t the scientific method great?). Here’s the output of five runs, with these controlling variables:

initial_performances = 1000

performances_per_day = 100

mean_value = 15 (feet, in our hypothetical long-jump scenario)

std_deviation = 3

starting_year = 1900

end_year = 2500

Outputs:

C:\Projects\helpers\sports_records>python records.py

Starting record: 23.9165133586

New record! Jan 19 1900 -> 24.0094301202 feet

New record! Jan 19 1900 -> 24.0403253856 feet

New record! Jan 25 1900 -> 24.1166650565 feet

New record! Feb 3 1900 -> 24.8525735138 feet

New record! Feb 17 1900 -> 26.3967518145 feet

New record! Apr 21 1900 -> 26.9566478399 feet

New record! Feb 21 1901 -> 27.1581347163 feet

New record! Nov 11 1901 -> 27.3669950219 feet

New record! Aug 6 1903 -> 28.3280704684 feet

New record! Nov 2 1903 -> 28.4759132311 feet

New record! Jul 27 1951 -> 30.8411657089 feet

New record! Feb 6 2131 -> 32.0021530025 feet

C:\Projects\helpers\sports_records>python records.py

Starting record: 23.4604203919

New record! Jan 20 1900 -> 23.7287133336 feet

New record! Jan 21 1900 -> 25.0489766323 feet

New record! Jan 21 1900 -> 25.2546913555 feet

New record! Feb 15 1900 -> 25.5985272675 feet

New record! Mar 17 1900 -> 26.3829300882 feet

New record! Apr 4 1900 -> 26.8377995825 feet

New record! Aug 25 1901 -> 26.9695746017 feet

New record! Dec 1 1901 -> 27.1512533653 feet

New record! Sep 22 1903 -> 29.1223906335 feet

New record! Jul 29 1963 -> 29.5489783756 feet

New record! Nov 23 1997 -> 29.7078403231 feet

New record! Feb 27 2017 -> 29.7674052672 feet

New record! Feb 7 2039 -> 30.0370404218 feet

New record! Jan 3 2044 -> 30.4896090469 feet

New record! Aug 4 2387 -> 32.9776158114 feet

C:\Projects\helpers\sports_records>python records.py

Starting record: 24.2168451485

New record! Jan 12 1900 -> 24.5874732389 feet

New record! Feb 15 1900 -> 24.7841308781 feet

New record! Feb 20 1900 -> 25.020299713 feet

New record! Mar 14 1900 -> 25.3808627765 feet

New record! Apr 3 1900 -> 27.0714857593 feet

New record! Apr 7 1900 -> 28.1360506817 feet

New record! Dec 9 1907 -> 28.8151692552 feet

New record! Nov 17 1921 -> 30.6336961373 feet

New record! Apr 25 2245 -> 30.9233783283 feet

C:\Projects\helpers\sports_records>python records.py

Starting record: 24.3837742479

New record! Jan 21 1900 -> 24.6502714838 feet

New record! Mar 8 1900 -> 25.1936144713 feet

New record! Apr 10 1900 -> 25.7547093986 feet

New record! May 28 1900 -> 25.8508940337 feet

New record! Jul 5 1900 -> 26.3613685958 feet

New record! Sep 11 1900 -> 27.0509325159 feet

New record! Jan 19 1904 -> 27.7846118667 feet

New record! Feb 12 1908 -> 28.3945403156 feet

New record! Jul 11 1920 -> 28.9648056412 feet

New record! Jun 20 1972 -> 29.1496234274 feet

New record! Oct 12 1981 -> 29.4548964992 feet

New record! May 17 1993 -> 29.6766835337 feet

New record! Jul 29 1999 -> 30.8707529494 feet

C:\Projects\helpers\sports_records>python records.py

Starting record: 23.8323407125

New record! Jan 8 1900 -> 24.3882377247 feet

New record! Jan 21 1900 -> 26.0946425885 feet

New record! Feb 16 1900 -> 27.6423250287 feet

New record! Nov 3 1902 -> 27.870732988 feet

New record! Nov 1 1907 -> 28.2679189241 feet

New record! Apr 5 1909 -> 28.4955439846 feet

New record! Dec 2 1910 -> 28.7639497232 feet

New record! Apr 0 1925 -> 29.164530551 feet

New record! Feb 4 1927 -> 30.3636285822 feet

New record! Jul 26 2044 -> 31.2504337489 feet

I think these results show pretty clearly that your reasoning does not hold up. I’ll paste the whole source for the script here (next post), so you can scrutinize it all you want, and test with different controlling variables and see the results for your self. (Just download and install python, open a command prompt and run python.exe records.py – any geek worth his salt should be able to do this without further instructions)

Nothing you’ve said refutes anything I said. In fact, you agreed with me:

“as the small bell curve gets larger and larger, the next step in the larger bell curve is just a tiny increment of the previous smaller bell curve, so the time interval between each record setting will tend to increase further and further.”

Obviously that’s true, I’m not entirely dim. However an increase is still an increase, and it will continue to be an increase each year.

Indeed I do agree with you in this regard, but in your post it seems as though you are implying that they will keep being broken with roughly the same frequency as they always did, and that’s really not the case – the time between each break will rise exponentially, and will eventually reach an average of centuries and millenia or more to get broken (more than the age of the universe! for some…)

import random

#—————————————–

# Test setup – change these at will

# Atletes setup

initial_performances = 1000

performances_per_day = 100

# Sports values

mean_value = 15 # Feet in long-jumps, or what-haves-you

std_deviation = 3

unit = ‘feet’

# Simulation timeline

starting_year = 1900

end_year = 2500

#—————————————–

current_record = 0

cur_year = starting_year

# Check if generated data_point is a new record and print stuff

def check_record(data_point, month = None, day = None):

global current_record

global unit

if data_point > current_record:

current_record = data_point

if month is None: return

print (“New record! ” + month + ” ” + str(day) + ” ” + str(cur_year) + ” -> ” + str(current_record) + ” ” + unit)

# Startup initial performances

for i in range(initial_performances):

data_point = random.normalvariate(mean_value, std_deviation)

check_record(data_point)

print (“Starting record: ” + str(current_record))

# Simulate yearly performances

while cur_year < end_year:

for month in ('Jan', 'Feb', 'Mar', 'Apr', 'May', 'Jun', 'Jul', 'Aug', 'Sep', 'Oct', 'Nov', 'Dec'):

for day in range(30):

for i in range(performances_per_day):

data_point = random.normalvariate(mean_value, std_deviation)

check_record(data_point, month, day)

cur_year += 1

Python is indentation dependent, and posting here messed-up the indentation. Unfortunately, there’s no edit button (and no help link for what tags are allowed in the comments to paste pre-formatted text, and no preview function, so I can re-post it correctly)

If someone knows the tags and how to re-post this properly, please do so (after properly fixing the missing indents)

Nice simulation, Petrucio. It’s interesting that in all but one of your posted runs the last record is substantially bigger than the second-to-last record. So for a long time, people may think that the record is unbreakable, and then someone breaks it by a foot.

Suppose the current record is X feet. The next record must exceed that, so it must be in the tail of the normal distribution starting at X. The probability that the new record will exceed X by more than a foot gets smaller as X gets larger.

To clarify, the tail starts at X, not the normal distribution.

Yes, you can clearly see the ‘outrageous’ headlines the media would put of for some of those sport results.

Though I’ve run some other tests with other variables, and I suspect that the artifact you are referring too is just a fluke is this data set.

Go ahead, generate on own data, post the results here!

My results were similar to yours. I posted the theoretically expected progression of records. The increments should get smaller, but surprisingly not by much, from about one foot at the beginning to about half a foot by the end. Even when the record is 6 standard deviations above the mean, there’s still a good 12% chance that the next record will beat it by a foot, but you might have to wait several thousand years for it because the time intervals increase exponentially.

15.0000

22.5228

23.5223

24.3304

25.0464

25.7037

26.3174

26.8962

27.4456

27.9695

28.4708

28.9520

29.4150

29.8614

30.2928

OT,but has anyone else noticed that the typewriter keyboard in the Skeptiblog banner has Q W E R T Z… ?

Is there some cryptic thing going on there?

Tmac, you just had to ask the “Y” question, didn’t you? The big philosophical questions always are the “Y” questions, aren’t they? :)

Just ran across this,to answer my own question (don’t you just love the internet?):

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/QWERTZ

Ahh, so Skeptic blog uses an East European socialist keyboard. Shermer missed this? :)

Great post Brian, and for the most part i agree with you. However, I found it ironic that you used the sport of long jump as an example; Mike Powell’s 8.95 metre record will celebrate it’s 20th birthday this year! You write in the article that it’s ‘more probable’ that a better performance would have happened the next year, I just wonder (and please excuse me for being a stats noob) how statistically likely a better performance the next year was in the case of a freak record like this?

Keep up the great work, I’m a massive fan.

alex

No, there is no particular likelihood of a record happening in the subsequent year. What is more likely is that {the set containing the history of the sport through Mike Powell’s jump PLUS any number of subsequent years} is more likely to contain a better performance than {the set containing only the history of the sport through Mike Powell’s jump}.

Sorry Brian,

Your impeccable logic, while right under certain circumstances, does leave a big ol’ door open for wrongness to walk right in :)

If you go from 1000 players in year X to 1001 players in year X+1, you will get a more performances that year, and on the face of it more chance at a record performance – but only if the count of past performances is large (>1 million man-years thereof in this case) – when there are less than that, the chance actually gets less.

Imagine year 1 of a sport. That year is certain to claim a record, but year 2 is not: with no growth in the sport the chance is 50% with a 100% growth the chance is 66.7% – but either way it’s less than year one. The same logic means that for all sports the chance of a record (all else being equal) starts with a decline which can only be reversed, after some time, by a growth rate in the sport, though it needs to be a rather big growth rate for this to happen on any useful timescale…

If I am wrong, then I’ll hand the question over to you. Which is more likely to contain the best performance: 101 years of performances, or a 100 year subset of it?