by

Donald Prothero, Sep 04 2014

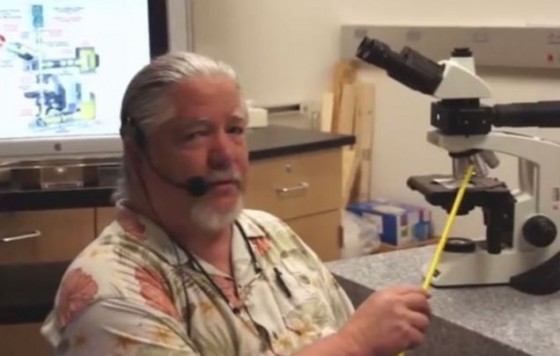

CSUN lab technician Mark Armitage, was fired after publishing creationist ideas and preaching creationism in his Biology Department job

A few weeks ago, a story broke in the news about a creationist working in the Biology Department at California State University Northridge (CSUN), who was fired for pushing creationism in the department. The story exploded across the internet, especially among the creationist organizations who are once again claiming persecution by scientists. CSUN apparently botched both the hiring of this guy, and now his dismissal, so they’ve been sued and this is going to play out badly for them in the courts. But the entire case raises larger issues that are not easily resolved.

First, the facts of the case. The plaintiff is Mark H. Armitage, a microscope technician (not a professional biologist). He did some undergrad work in Biology at University of Florida, but didn’t graduate. Then he got his B.S. in Education from Jerry Falwell’s fundamentalist Liberty University, and his M.S. in Biology (parasitology) from the Institute of Creation Research, an unaccredited fundamentalist organization that has since left California and closed down its graduate program. As many others have shown, the ICR “Master’s Degree” was a sham, consisting of little more that incompetently done book reports and quote-mining from legitimate scientific literature with a creationist spin, not legitimate scientific research. I’ve seen a number of “master’s theses” from there—they are so bad they wouldn’t even pass for a freshman book report. Prior to his employment at CSUN, he was employed as a microscope technician at a variety of Christian schools. But he has no Ph.D., no formal training or peer-reviewed published research in the histology he was working on. He’s just a humble lab tech on a 2-day a week part-time gig, with no guarantee of employment from one semester to the next. His sole job is to maintain and keep track of the microscopes in a big department with hundreds of them, not to teach courses or do research. Continue reading…

comments (28)

by

Donald Prothero, Jan 29 2014

Ever since I was a 4-year-old, hooked on dinosaurs, I knew that I wanted to study paleontology for the rest of my life. By the time I was in fourth grade, I was the only kid in my school who knew anything about dinosaurs (this was in the early 60s, before dinosaurs became cool for kids). I was asked to lecture about them to the sixth graders, and so I knew I liked to teach. Once I got into college and followed the normal route to a career in paleontology through my Ph.D. at Columbia University and the American Museum in Natural History in New York, I was committed to becoming a college professor. Starting with teaching at Columbia and Vassar, then at Knox College in Galesburg, Illinois, and then 27 years at Occidental College in Los Angeles, and at Caltech in Pasadena, I’ve been extremely fortunate in teaching at elite institutions with outstanding students every place I’ve worked. Most of my time has been spent in small private liberal arts colleges (Vassar, Knox, and Occidental), where the classes are small and full of dedicated, bright students who mostly want to learn and generally work very hard. I got to know every student in nearly every class very quickly, and got to be good at reading their faces to make sure they understand. I always challenged them without pushing them past their breaking point. I was very proud of the mature, thoughtful scholarship our senior geology majors would produce after four years of the best teaching and opportunities. I’ve been nominated for teaching awards many times and won a few times, and I always have alumni and alumnae coming back and telling me how important my class was in opening their eyes or changing their lives. At small private colleges where the tuition is high, we give them their money’s worth with highly intensive, personalized education (I have involved hundreds of students in my research over the years, and about 45 students have more than 50 published scientific papers co-authored with me). We know immediately if a student is missing from class (it’s hard to hide in a class of eight, but even in a class of 32, I kept track). The college practically flipped out if a student missed 2-3 meetings in a row without contacting us—we were instructed to notify the Dean of Students for any student doing poorly on a test, or showing signs of slipping, since they don’t want anyone to drop out if they can help it. And we were proud of our high retention rate, and virtually all our students graduated in four years. Continue reading…

comments (39)

by

Brian Dunning, Mar 14 2013

STEM = Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics.

STEM = Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics.

The STEM fields are of special significance in the United States, as they are considered by the government to be strategically important, and because we have a shortage of experts in these fields. As a result, many government and educational agencies have STEM programs, and we’ll discuss some of those in a moment.

My purpose today is to nip a growing trend in the bud, which is the tendency for people involved in the arts to expand it to STEAM (A = Arts). Nearly everyone in my family (except me) is musical, and so I sit through a lot of fundraising presentations at concert halls, always hearing the pitch of why STEAM fields are so important. It’s in the high school newsletters, it’s in the local performing arts community brochures; it’s everywhere you look when you go to an art show. Continue reading…

comments (157)

by

Daniel Loxton, Oct 16 2012

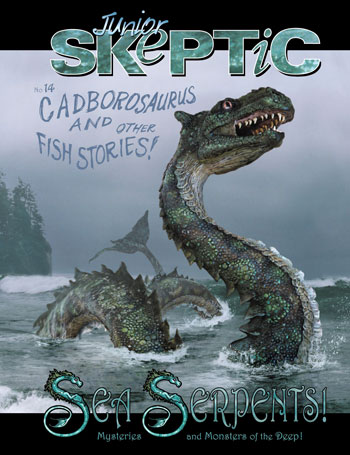

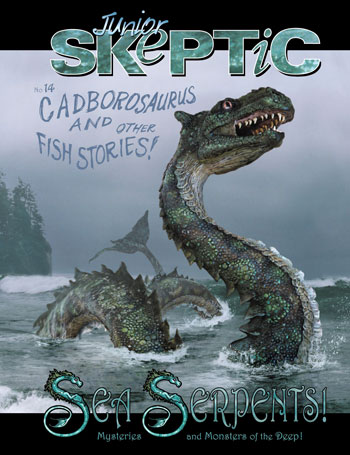

Just for fun, I’d like to share a small anniversary with you: this month marks 10 years since I turned in my first cover illustration for my first issue of Junior Skeptic (bound within Skeptic magazine). It’s an especially meaningful occasion for me because I usually consider myself an artist first (or at least an illustrator) and a skeptical writer second.

Just for fun, I’d like to share a small anniversary with you: this month marks 10 years since I turned in my first cover illustration for my first issue of Junior Skeptic (bound within Skeptic magazine). It’s an especially meaningful occasion for me because I usually consider myself an artist first (or at least an illustrator) and a skeptical writer second.

Featuring Cadborosaurus (Vancouver Island’s own regional, West Coast iteration of the Great Sea Serpent of the North Atlantic), this cover was something of a labor of love. It was my first shot at Junior Skeptic, as a one-time thing. It could only be about Cadborosaurus. I’ve previously described how I (like many skeptics) came to the skeptical literature as a direct continuation from my passion for paranormal mysteries. Of all paranormal topics, cryptozoology bit hardest and deepest—and of all the roaring, stomping, kickass (yet elusive!) cryptids to fall for, I have always most loved Cadborosaurus. An 80-foot sea serpent sliding undetected through the very waters off my childhood home? A cryptid I might glimpse while roasting marshmallows on a storm-swept beach? Who could resist—especially when my own parents once saw Cadborosaurus with their own eyes?

Continue reading…

comments (1)

by

Daniel Loxton, Oct 15 2012

Click for Ankylosaur Attack listing at Shop Skeptic

I’m very excited to announce that Ankylosaur Attack, my first paleofiction storybook for young children (illustrated with Jim W.W. Smith) is among the 2013 Forest of Reading® Silver Birch® Express Award nominees revealed this morning by the Ontario Library Association. This will make the book part of Ontario’s province-wide school and library reading program—the largest such program in Canada.

I’d like to express my immense gratitude to the Ontario Library Association for this nomination (and of course to my publisher, Kids Can Press). The Forest of Reading awards are exceptionally competitive in every category, and it’s an honor to be in such fine company. (My nonfiction Evolution: How We and All Living Things Came to Be was nominated for the Silver Birch nonfiction award, which went that year to my friend Valerie Wyatt—Editor of both Evolution and Ankylosaur Attack, and veteran of over a hundred other children’s books).

Continue reading…

comments (5)

by

Donald Prothero, Sep 05 2012

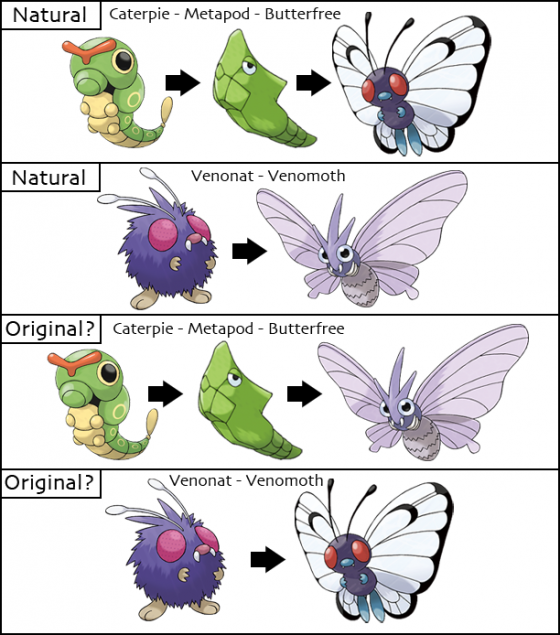

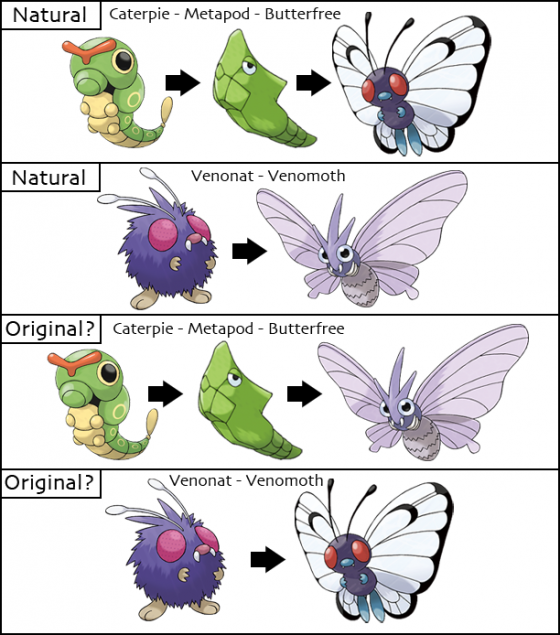

Pokemon is full of interesting “evolving” sequences of form, some of which resemble normal ontogeny of metamorphosing insects

The dogs days of summer were finally ending, and I was glad. The heat waves that have fried the U.S. all summer long were still hanging on in late August. The kids were trapped inside the house in the air conditioning, since there’s no way to play outside in the 105-degree heat, humidity, and smog, and even running an errand is unpleasant and potentially dangerous when the car is 140 degrees inside after you open it. Besides, there’s no place to go for them to get exercise in the air conditioning: they’ve outgrown McDonalds play lands, and I don’t want to spend money in a mall or in those overpriced indoor entertainment complexes. The boys had a few days left before school starts, and then they resume a regular healthy routine, and they’re occupied again. In the meantime, they lounged around the house in their pajamas till afternoon, with the TV blaring Cartoon Network non-stop while they play with and build their Legos. Any time we suggested an activity for them, they may engage for a while, then it’s back to goofing off. It’s summer, they’re kids, and they have no obligations. We already did the family trip to Colorado for my field work, and had our planned activities back in June and July. And I was counting the days until they were back in school and on a healthier routine.

Continue reading…

comments (22)

by

Donald Prothero, Aug 15 2012

Life is what happens when you’re busy making other plans

—John Lennon

Forty years. In some contexts, it’s not very long, but in the span of a human lifetime, it’s huge. Only a few generations ago, most humans did not live past their 40th year, and in some parts of the developing world, they still don’t. However, in the Western World, most of us can not only assume that we’ll live at least 40 years, but many of us will survive for 80 years or more. Still, 40 years is a long span of time, when most people can assume that life will have changed in many ways and thrown a lot of surprises at them.

Yours truly, 40 years ago: a skinny, nerdy kid with thick glasses and no social skills…

Last weekend, my high school class (Glendale, California, High School Class of ’72) had their 40th reunion. It was a real eye-opener for me. I missed the 5th year reunion in 1977 because I was in grad school at Columbia University in New York, and the tenth reunion because I was in my first teaching job at Knox College in central Illinois. I made the 20th reunion, but sometimes our class couldn’t get their act together, so there was no 15th, 25th, or 30th reunion that I know of. The last reunion before this one was the 35th, which was the first time I’d really seen most of my classmates in a long time. Then the big FOUR-OH came up, and a lot more of them made the effort to show up from around the world, and reconnect with people they’d grown up with. Most of them were not just my high school classmates, but I first met them in elementary school over 50 years ago, so we went back a LONG ways. Like in every reunion, it’s a mixed bag: people who I’ve remained in contact with over 40 years, but seldom see; people who I’d lost touch with since 1972, but we had once been close friends; many people whom I barely knew in high school, but I had to be friendly and try to remember them; and a surprising number of “guests” who came to the reunion who were just plain weird (along with a bunch of drunks in the back of the room). Time had not been kind to many of us. Some had aged much more than others, so I could barely recognize them without trying to squint at their tiny name badges (complete with our senior photos, which further cruelly reminded us of how much we’d all changed). But I was also reminded how I was a skinny nerdy kid with thick black glasses back then, excluded from the major social cliques, and so I feel fortunate that time hasn’t turned my hair gray yet or caused much hair loss, and I’m no longer underweight. (But I’m even more near-sighted than back then). I also was shy and awkward, and had difficulties relating with people back then, whereas after 40 years I was much more comfortable with these people I’d known since childhood. Continue reading…

comments (14)

by

Brian Dunning, Jun 07 2012

Appealing to the target demographic

Bigfoot and aliens — groooan — are so outdated. Right?

Yes and no. They’re outdated, so far as the amount of work left to do to educate the general public; almost nobody takes them seriously anymore. But they’re not at all outdated as far as being in the public consciousness. Almost everyone knows about them, and that’s critical to the mission of science education.

To make headway in critical thinking, we need to start with common ground from which it’s easy to see the reasons why a given subject is unscientific. It’s easy to talk about Bigfoot with almost anyone and have them agree to the low value of anecdotes, logical red flags, and (thanks to the current TV show) the unreliability of ideologically motivated proponents. Continue reading…

comments (38)

by

Donald Prothero, Apr 18 2012

Having taught for 33 years at small nationally-ranked liberal arts colleges (Vassar, Knox, and Occidental) where teaching is a priority over research, I’ve seen pedagogical fads come and go. It seems like every 2-3 years the college brings in some pedagogical “expert” to tell us experienced professors that we were doing it all wrong for years, despite the excellent responses and teaching evaluations that we receive. I’ve sat through endless committee meetings and workshops where they try to get us to follow their “one size fits all” approaches to pedagogy. In some fields where discussion of everyday experience is the norm, they insist that we should make every class a discussion section, and let students “discover for themselves” what the field is about. I’m all in favor of “active learning,” as the current fad is called, but there are limits to where it is applicable. Some subjects, such as most of the natural sciences, are “content-heavy” and require that the students be exposed to a certain minimum amount of material, or they cannot take the next course in our highly structured and sequential curriculum. We try to make up for it by giving students all the “active learning” we can in lab sections, where they handle the materials and do the experiments themselves. But even in a small liberal arts college where the largest lecture section is limited to 32 students, it’s a severe challenge to “cover the material” and expect the student to also take an active role in every lecture. When some humanities professor tell us science faculty that we should turn Intro Chemistry into a non-stop discussion section, we all just laugh at their cluelessness. Not only do we have the constraints of a large amount of material to cover so the student can take the next course in the sequence, but in the case of chemistry and biology, there are MCAT and GRE exams that also have an expectation of a certain amount of “content” mastered by the students’ third year. Nonetheless, the reality is that the content-driven lecture is an essential element of at least some college courses. You may be able to get away from them in some subjects in the humanities and social sciences where every person has at least some valid expertise or ability to form an opinion, but it won’t work with a lot of the material we cover in the natural sciences, since so much of it is alien to one’s everyday experience and few students could have a meaningful debate about the merits of some reaction in organic chemistry.

This is not to say that I don’t integrate “active learning” techniques in my lecture whenever I can. They can range from simple things like passing a specimen of a rock or fossil around and make sure they are all see or feel what I’m describing; or getting them to all stand up in their seats, and then having the men and women sit down in 2:1 ratios as if they were atoms paired up into crystals and settling out of a magma chamber. I frequently pose questions to the class and wait patiently til someone comes up with the answer, giving them a few hints along the way if necessary. I’ve got amusing cartoons that make the point interspersed here and there through my slides; I try to make sly references to cultural phenomena or things the students can relate to, or poke fun at familiar movie plot devices that are geologically impossible. I try to pose realistic scenarios (especially on exam questions, which are all essay style) so that they can show they understand how their knowledge applies to the real world, and not just how well they can memorize and regurgitate a list of facts.

Continue reading…

comments (22)

by

Daniel Loxton, Jan 24 2012

Working on refinements to my upcoming cryptozoology book with Skepticblog’s own Don Prothero (due out later in 2012) gave me a chance yesterday to dip back into Harvard psychologist Susan Clancy’s fascinating 2005 book about her studies of alien abductees, Abducted: How People Come to Believe They Were Kidnapped by Aliens. I thought I might share a couple of passages from the book here, partly because they dovetail so nicely with my own “Reasonableness of Weird Things” arguments.

Working on refinements to my upcoming cryptozoology book with Skepticblog’s own Don Prothero (due out later in 2012) gave me a chance yesterday to dip back into Harvard psychologist Susan Clancy’s fascinating 2005 book about her studies of alien abductees, Abducted: How People Come to Believe They Were Kidnapped by Aliens. I thought I might share a couple of passages from the book here, partly because they dovetail so nicely with my own “Reasonableness of Weird Things” arguments.

Clancy’s area of primary interest is not skeptical investigation of paranormal claims, but false memory. To perform an “honest broker” service as thorough and reliable guides to the evidence on paranormal topics, skeptical investigators are ethically obliged to seriously consider the (unlikely) possibility of paranormal phenomena. In her own work with abductees, Clancy’s obligations were different. She felt justified in taking it pretty much for granted that her subjects had not been kidnapped by space aliens. Abductees were, for Clancy, a proxy group to allow her to examine questions related to a separate population’s “recovered” memories of childhood sexual abuse.

Research into abuse is of course very complicated—and ethically fraught. It is surrounded by tension and the potential for harm for the simple reason that abuse really happens. By contrast, Clancy wrote,

…alien abductees were people who had developed memories of a traumatic event that I could be fairly certain had never occurred. A major problem with my research on false-memory creation by victims of alleged sexual abuse was the fact that it was almost impossible to determine whether they had, in fact, been abused. I needed to repeat the study with a population that I could be sure had ‘recovered’ false memories. Alien abductions seemed to fit the bill.1

Continue reading…

comments (27)

STEM = Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics.

STEM = Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics. Just for fun, I’d like to share a small anniversary with you: this month marks 10 years since I turned in my first cover illustration for

Just for fun, I’d like to share a small anniversary with you: this month marks 10 years since I turned in my first cover illustration for

Working on refinements to my upcoming cryptozoology book with Skepticblog’s own Don Prothero (due out later in 2012) gave me a chance yesterday to dip back into Harvard psychologist Susan Clancy’s fascinating 2005 book about her studies of alien abductees,

Working on refinements to my upcoming cryptozoology book with Skepticblog’s own Don Prothero (due out later in 2012) gave me a chance yesterday to dip back into Harvard psychologist Susan Clancy’s fascinating 2005 book about her studies of alien abductees,