Pluto, Triceratops, Brontosaurus:

What’s in a Name?

What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.

ITEM: A few years ago there was a big fuss in the media about the fact that astronomers had demoted Pluto from one of the classic nine planets to a “minor planet,” just another body in the solar system. Some people were shocked and upset, since they had always learned that Pluto was the ninth planet and didn’t want to unlearn it, no matter what astronomers said. Astronomers pointed out that numerous other small icy objects had been found in the Kuiper belt outside Neptune, including some that were larger than Pluto—but no one was ready to promote 2060 Chiron to the 10th planet. Instead, the logical solution was to demote Pluto to the class of “dwarf planets” along with these other objects, since it really didn’t have much in common with the other eight planets. The state legislatures of Illinois (where Pluto discoverer Clyde Tombaugh was born), New Mexico, and California passed resolutions against the change (despite the fact they had no legal authority in the matter). Caltech astronomer Mike Brown, who spearheaded the change, wrote in his book How I Killed Pluto and Why it Had it Coming that “I’ve been accosted on the street, cornered on airplanes, harangued by e-mail, with everyone wanting to know: why did poor Pluto have to get the boot? What did Pluto ever do to you?” In 2007, the American Dialect Society recognized the neologism “to pluto” (meaning “to demote or degrade”) as the 2006 Word of the Year.

ITEM: In 2010, paleontologists Jack Horner and John Scannella suggested that Triceratops was just the juvenile form of the longer-frilled dinosaur Torosaurus. Once again, there was public outrage and protests. People complained that their beloved three-horned dinosaur was being snatched away from them. Unfortunately, the public and the media got the story completely backward. IF other scientists eventually agree with Horner and Scannella, and formally decide to ratify the idea that Triceratops and Torosaurus were the same animal, then the invalid name would be Torosaurus, not Triceratops. As Brian Switek pointed out in his blog “Relax—Triceratops really did exist”, Triceratops was named by Yale paleontologist O.C. Marsh in 1889; the same scientist named Torosaurus in 1891. According to the rules of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN), Triceratops has priority over Torosaurus, so no one will weep or gnash their teeth if Torosaurus becomes the invalid synonym and is officially demoted.

ITEM: For generations, people learned that one of their favorite dinosaurs was called Brontosaurus or “thunder lizard.” However, in more recent years popular dinosaur books are catching up with the science and using the correct name Apatosaurus (“deceptive lizard”). Why the change? Once again, the problem was due to Yale paleontologist O.C. Marsh and the common practice at that time of giving every single distinctive fossil a new taxonomic name (today we call them “splitters”). As Brian Switek and Stephen Jay Gould have pointed out, the first skeleton of this creatures was a relatively incomplete juvenile specimen which Marsh named Apatosaurus in 1877. Then his crews working in the same beds near Como Bluff, Wyoming, found a much more complete adult specimen, which Marsh named Brontosaurus in 1879. The second specimen was the best sauropod skeleton ever found up to that point, so it was soon mounted at the Yale Peabody Museum, and displays of other skeletons at the American Museum in New York and the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh also called their specimens Brontosaurus. This image was strongly embedded in popular culture, so that not only every museum mount, but also popular books and movies, kids’ dinosaur toys, and even the logo of the Sinclair Oil Company was called “Brontosaurus“.

However, in 1903 paleontologist Elmer Riggs began to rethink the oversplitting typical of paleontologists of Marsh’s generation, and recognized that Apatosaurus and Brontosaurus were the same thing. Again, according to the ICZN rules of priority, the first name given is the proper name, so Apatosaurus is the senior synonym of “Brontosaurus” and paleontologists have accepted that verdict ever since Riggs published his work in 1909. In 1975, Jack McIntosh and Dave Berman re-examined all the apatosaur fossils, and confirmed Riggs’ determination. (They also discovered that the wrong skull, resembling the skull of a Camarasaurus, had been put on the mounted specimens; Apatosaurus had a long-snouted slender skull much like that of Diplodocus). As far as paleontology is concerned, the question was settled in 1909, and no well-informed dinosaur paleontologist has used the name “Brontosaurus” for many decades. But the name was well entrenched in the popular mind due to all the books and toys and paraphernalia that had used the name “Brontosaurus“. In 1989, the U.S. Postal Service created a stir when it issued a “Brontosaurus” stamp, and paleontologists cried out in protest that the postman should recognize scientific principles, not cater to popular misinformation. As a response, Stephen Jay Gould wrote his famous essay, “Bully for Brontosaurus“, where he too argued a preference for the old familiar name, even though he admitted that by the rules of the ICZN, Apatosaurus was the correct name and “Brontosaurus” was invalid.

What do all these controversies over the proper names of objects have in common? In each case, they are examples of older names or concepts (“Pluto is the ninth planet”) that the popular audience learns usually early in their childhood, but have become scientifically incorrect or outdated. Scientists are guided by strict rules as to which name is proper, or why some objects can be considered planets and others cannot. As scientists learn new things, or re-examine old ideas, their conclusions change, and with these new concepts come changes in the names of things as well. Although scientists might wish to preserve the old and familiar, if the evidence is clear, then scientists must abandon ideas or names that have become outdated, and accept the new names or concepts.

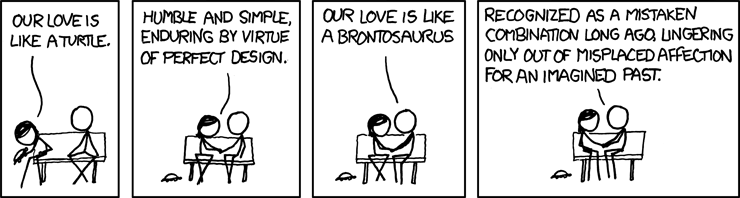

The public, on the other hand, operates by different rules. They typically learn scientific factoids by rote early in their school years, and hate it when some eternal truth that they remember from childhood has now been thrown out. This is revealed by the deep emotional reactions these decisions evoked, such as T-shirts with Triceratops and the slogan “I still believe”, or the strong reactions Mike Brown encountered from disgruntled Pluto fans. On Facebook’s “Save the Triceratops” page, someone posted, “Triceratops is friggin’ awesome. People love Triceratops. They love the funny way their children mispronounce Triceratops. I love all of it, too. I like the name Brontosaurus more than the name Apatosaurus. The thought of Triceratops being an invalid name is not cool to me. I wouldn’t like it.” Or, as the xkcd web comic put it, “Our love is like a Brontosaurus, recognized as a mistaken combination long ago, lingering only out of a misplaced affection for an imagined past.”

Such decisions may not be popular, but they are part of the learning process in science. Scientific hypotheses must always be tentative, and must be subject to revision if better evidence comes along. Few people appreciate this, but instead are raised with the mistaken notion that science is about stable “final truths” that never change—until scientists change one of their favorite dinosaurs or planets. Then people react emotionally rather than rationally, mostly because they do not understand the reasons behind the scientific decision, or how science really works in the first place.

As Robert Krulwich put it in his blog “The Triceratops Panic: Why Does Science Keep Changing its Mind?”

People don’t want their eternalities to change. They hate that. But, in the end, science has to win. There are 5 year olds all over the world now growing up with Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Neptune and Uranus, but not that other guy, the one with the name of Mickey Mouse’s pet dog. In fifty years, Pluto may be just a dog again. That’s how it goes.

If you think that it upsets people when science changes its mind, look what happens when religion does. Wars have been fought.

Which itself is a bit odd. Aren’t religions supposed to incorporate eternal truths? The First Council of Nicaea settled how to calculate the date of Easter. So before that, the date of easter was an ‘eternal kludge’? (Oh, and of course to squash that pesky bunch of Arianists).

Changes continue all the way up to the present where you can have women priests now – gasp! Whatever next – primate primates?

“primate primates?”

Isn’t that already the case? =P

The Pluto thing really does bamboozle me, so coming across someone who was passionate about Pluto’s planetary status was something I didn’t really expect.

I can’t help but face palm every time I hear about people trying to legislate science. Even attempting to do that is such a gross misunderstanding of what science is. I can only cringe that so many would try to participate in it. Argumentum ad populum is the way we are going to decide how things work? Ugh.

I wonder if the rejection of a democratic approach to science is part of what makes people think scientists are elitists. The mass education just needs to continue, I suppose.

Definitely. At some point people starting accepting all opinions, including their own, as equal. This regardless of the data and the conclusions of experts.

Worse, armchair opinions are more equal than others.

I suppose the rise of relativism (post-modernism) was essentially a rebellion against science.

It takes time for people to change cherished habits. My grandfather could never stop saying “negro” long after it became very non-PC and not used by most people. As someone who has always had a love for science and strong interest in new discoveries, i just stopped referring to Pluto as a planet and moved on. Brontosaurus was harder to abandon because i like the sound of it, but i completely agree with the reasons for calling it Apatosaurus.

I think the closest analog to this is “Han Shot First”

It has little to do with science (or religion) – but rather the psychology of fandom. Geeks pride themselves in knowing all of the minute irrelevants details of some particular topic (be it Star Wars or anything else). When those details change, they get upset. Why this happens is something for a longer discussion, but suffice to say they do.

Things like the names of the planets and the names of dinosaurs are one of the first things we geek out about. As children we all took pride in being able to name all the planets and being able to name all the dinosaurs. We were all geeks at that age.

When scientists come along and change these things, it feels just like George Lucas coming along and saying “Han shot first”. And it produces a similar emotional reaction.

Han DID shoot first! Lucas changed it so Greedo shot first.

“There are 5 year olds all over the world now growing up with Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Neptune and Uranus, but not that other guy, the one with the name of Mickey Mouse’s pet dog.”

Uranus? I thought it had been renamed Urrectum.

Popular pushback against new scientific names seems to occur only when people adopt the official term as their everyday one, then suddenly see it changed. There was no stir when taxonomists decided that *Perca huro* was not really a perch, but a member of the sunfish family, and renamed it *Micropterus salmoides*. Fishermen didn’t care. Most of them didn’t even notice. They just went on calling it a largemouth black (or bigmouth, or lineside) bass.

Can I just say here, Chris, for one moment, that I have a new theory about the apatosaurus?

This theory goes as follows and begins now. All apatosauruses are thin at one end, much much thicker in the middle, and then thin again at the far end.

That is my theory, it is mine, and belongs to me and I own it, and what it is too.

…ahem

(+3 internets to Anne Elk)

It feels awkward whenever a name you knew your whole life changes, whether it’s a person, a landmark, or a dinosaur. And when it comes to brands and sports teams, it seems the name is what matters most, since the players and coaches change.

In a sense, Clyde Tombaugh’s discovery of Pluto in 1930 was more significant than discovering “just” another planet. He discovered an entirely new and different type of object, but nobody realized it at that time. The reason that Pluto was discovered first is that it is the brightest trans-Neptunian object, as seen from earth. But it’s far from the only such object, and by no means the largest.

Can I just say here, Chris, for one moment, that I have a new theory about the apatosaurus?

This theory goes as follows and begins now. All apatosauruses are thin at one end, much much thicker in the middle, and then thin again at the far end.

That is my theory, it is mine, and belongs to me and I own it, and what it is too.

The reason there is so much objection to the controversial demotion of Pluto is that it was not done by a consensus of the world’s astronomers but by four percent of the International Astronomical Union, most of whom are not planetary scientists, in a process that violated their own bylaws and produced a horrible definition. Their decision was immediately opposed by hundreds of professional astronomers in a formal petition led by New Horizons Principal Investigator Dr. Alan Stern. It is unfortunate that the media obscures the fact that this debate is far from over. As an astronomer myself, I am working on a book of my own, “The Little Planet That Would Not Die: Pluto’s Story.” Look for it later this year.

I accept the fact that Pluto is no longer a planet, but that doesn’t mean I have to like it.

All that being said, 2060 Chiron was never really likely to be considered a candidate for a planet. 136199 Eris, on the other hand…. (although it was the discovery of Eris that was the catalyst for Pluto’s planetary demise).

I find the growing collection of Dwarf Planets to be the most interesting field of current astronomical research within the solar system, anyway.

The scientific community has zero public relations savvy. IF they did have any marketing skills and any sense of “cool”, space exploration would be a burgeoning enthusiasm on everyone’s lips, intelligent design would be buried under scorn and they’d realize the potency of names and labels.

So, there I am. One more correct answer and I win 1,000,000 dollars…Regis leans forward and says, “How many planets are there in our Solar System?

When I was a geeky kid, 1940s, I knew all of the countries in the world. Then, once every decade or so, they all changed names.

Don’t even start on the Brooklyn Dogers, or the Braves.

I accept the fact that Pluto is no longer a planet, but that doesn’t mean I have to like it