The Importance of Skeptical Scholarship

I’ve been winding down these last few evenings with a real treat: Benjamin Radford’s new book Scientific Paranormal Investigation. I expect to tackle a full review soon; for now, I’m getting a kick out of his unapologetic pitch for serious skeptical scholarship. It’s a topic I think about often, but rarely more than right this second — staggering as I am under the weight of my own current research.

I’ve been winding down these last few evenings with a real treat: Benjamin Radford’s new book Scientific Paranormal Investigation. I expect to tackle a full review soon; for now, I’m getting a kick out of his unapologetic pitch for serious skeptical scholarship. It’s a topic I think about often, but rarely more than right this second — staggering as I am under the weight of my own current research.

How important is scholarship for skeptics? Should skeptics know a lot about the paranormal literature (or, rather, the many niche literatures for the many niche paranormal topics)? And, does it matter whether we know much about the literature of skepticism?

When I’ve asked these questions in the past, I’ve received mixed responses. Some skeptics argue that vast encyclopedic knowledge is essential. Others claim that traditional skeptical expertise is more or less irrelevant to modern skeptical activism.

That wide range of opinion arises from the many kinds of skeptics pursuing their many kinds of projects. Some, like Ben Radford, are serious primary researchers, dedicated science communicators, or both. They wish to solve mysteries and inform the public, and they necessarily care about refining the best practices for achieving those goals. Of course, not all skeptics share those interests or responsibilities. Some are satisfied to indulge their own curiosity, or to hone their own critical thinking skills. Others view skepticism as a social scene rather than a research project — a way to find friends who accept their science-informed worldview.

Finding Stuff Out

Still, I’d suggest this as a general principle: the more willing we are to express opinions on skeptical topics, the more seriously we should pursue skeptical scholarship. When we take on a public role (even if only a Twitter stream or blog) we take on an ethical responsibility to strive for accuracy.

Even simpler, the ethos of skepticism calls for active rigorous investigation. I usually let Mark Twain’s “old and wise and stern maxim” say it for me: “Supposing is good, but finding out is better.”

In an important sense, the whole of the skeptical project over the past 35 years can be boiled down to that one single piece of advice. There’s no getting around it: finding out is better. I can’t think of any area of domain expertise where less knowledge is as good as more.

If we’re committed to finding out, then literacy in our field becomes very important indeed. It helps us to ask the right questions, and to avoid the wrong conclusions. As Radford explains,

Skepticism, like science or any other body of knowledge, works on precedent. Scientific paranormal investigators need not — indeed should not — approach a case without background information and having researched previous investigations. While the specific circumstances of a mystery may be unique in each case, the type of mystery is not. Any investigation, from aliens to zombies, monsters to mediums to miracles, has many earlier solved cases as precedents. … Researching and knowing the history of skeptical investigations into paranormal claims is not simply a matter of paying your dues; it is essential to conducting an informed investigation.

He’s right. When we consider pseudoscientific topics, it pays to know where they come from. The more we know about the roots of a mystery, its history and proponents and scandals and related claims and so on, the better (and more fair) our assessment is liable to be — and the better able we are to communicate responsibly about that topic. Moreover, the wider and deeper our general knowledge of pseudoscience, the better prepared we are to respond quickly to mutations of old ideas. (Bomb-detecting dowsing rods are a stark reminder that even the most harmless and hokey old chestnuts can reemerge in lethal new variants — which, thankfully, the James Randi Educational Foundation had the background to challenge.)

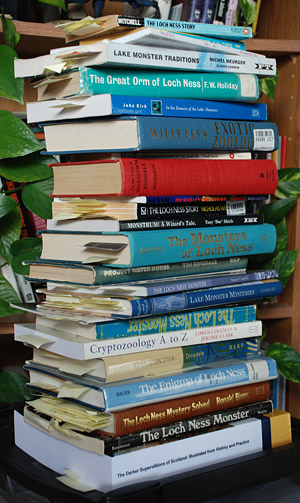

Some of the Loch Ness monster resources I've been digging into

Making Connections

At the moment, I’m busily digging into the Loch Ness monster literature for a book chapter. The challenge is that the literature on Nessie is so enormous (dare I say, “monster-sized”?) that even the most extensive reading must necessarily be incomplete. It’s daunting to realize the key information could always be one resource away. That’s the way it goes: each discovery spawns new questions, leading us deeper, giving us new perspectives on the vastness of our own ignorance. The more we learn, the less we know.

At the same time, the more we learn, the more connections we can make. Different threads of investigation have a way of leaping together and informing each other. (When this happens, I’m always reminded of science historian James Burke’s wonderful Connections series of documentaries and Scientific American columns.)

Finding connections is fun. Although I’ve researched Nessie before (it’s a lifelong interest), I’m happy to say that I’m digging out all sorts of neat stuff. You’ll have to wait for the book for most of that, but here’s a fun tidbit I just learned: it seems that Philip Henry Gosse (whose 1857 book Omphalos: An Attempt to Untie the Geological Knot underlies so much of modern creationist argument) was the guy who first proposed that sea serpent sightings might be explained by surviving populations of plesiosaurs (in his book The Romance of Natural History). Gosse influenced Rupert Gould, who wrote the first and most influential book on the Loch Ness monster. The links between creationism and cryptozoology are many, but I hadn’t realized that the Omphalos guy laid the groundwork for Nessie! That’s hardly smoking gun stuff (Gould discussed Gosse in the 30’s) but I didn’t know it before. Now I do.

Along the way, there are frequently unexpected chance discoveries on other topics altogether. Digging through newspaper archives over the past weeks (several academic portals, and several pay services), I incidentally happened across a wide swath of primary documents on crystal skulls, the Mokele-mbembe, Ogopogo, and other odd mysteries besides. Did you know about this satirical 1827 attempt (PDF) to prove that Napoleon Bonaparte was “nothing more than an allegorical personage”? Neither did I. (I’ll return to the topic of newspaper archives in a future post.)

Large or small, brand new to the literature or news only to us, discovery is a tremendously rewarding feeling. Radford urges us avoid “approaching research as necessary drudgery,” and instead to take pride, even joy, in the process of investigation. And then, every once in a while, the effort pays off big:

Sometimes you’ll find a “smoking gun” fact or document or photograph that proves that everyone is wrong about the topic. I’ve spent many sleepless nights while in the throes of an exciting investigation, my mind racing with the implications of the information I’ve discovered.

I’ve been there. Let me tell you, it’s quite the feeling when pieces of an unsolved mystery (no matter how small) suddenly click into place. For those who care about finding out, there’s a unique joy in finding out first.

Like Daniel Loxton’s work? Read more in the pages of Skeptic magazine. Subscribe today in print or digitally!

This is much better than what I had in mind. A practically poetic way to make an important point.

Would you please say something stupid soon so that I can point it out? I’m starting to sound like Paula Abdul, here.

Do you ever get the feeling that the time spent researching Nessie could be better spent researching just about anything else? Auto repair, finance, alternative medicine…

I research a lot of topics, including alternative medicine (as here and here). In answer to the more general question: No — I actually think that time researching paranormal topics is well spent. I make my pitch for the value of traditional paranormal skepticism here (PDF), but one answer is that other people already do finance and auto repair.

Do you want to make more money? Of course. We all do. So find out how easy it is to train at home for a better career. At ICS, more than 9 million men and women have trained at home for a new career without setting foot inside a classroom. And now at home, in your spare time, you can get your high school diploma or even your degree. Choose from any one of these courses:

High School

TV/VCR Repair

Computer Programming

Child Day Care

Book Keeping

Gun Repair

Electrician

Legal Assistant

Veteranary Assistant

Interior Decorating

Medical/Dental Assistant

Art

or get your degree. You can major in Business Management or Accounting.

Make this important call right now.

Good job beating the spam filter.

I think he was ridiculing your challenge that Daniel was wasting his time. But I’m sure you got that

Dang!!! I wonder if it’s too late to get my money back from ICS?

I would say that having folks spend time on things like attempting to find Nessie, researching Ghosts, etc, etc, all from a skeptical, and VERY scientific stance is one of the best resources we have, not only for skeptics, but for society.

Humans love to buy into very odd, and sometimes highly dangerous things. Having the data to show, if odd claims *could* be true or not, is something we need.

And, there are already tons of people doing those other things, and not one skeptical researcher I have ever met would tell people to NOT learn to do some other trade, if that is what you want to do. ;)

I use to be of the mindset, that cryptozoology research seemed like a waste of time. I don’t know of anyone who believes in Loch Ness, Bigfoot, etc. – even among some of my most credulous acquaintances.

But since I’ve been listening to MonsterTalk, I find the processes of the research to be very useful. The methodology, the assumptions, the puzzle-solving (calculating distances, sizes of shadows, etc.) has been interesting and educational. It’s mystery-solving, forensics, and a bit of sci-fi all in one.

Yeah, but one can research things that more people believe and that cause more harm, like medical quackery, conspiracy theories, and free energy machines.

There’s some research methods that are somewhat specific to cryptozoology though. Forensics, pictures, video, examinations, are all helpful for skeptics when critically examining claims. UFOs and ghosts have some cross-over to this, but it doesn’t allow for looking at evidence from a biological standpoint.

I suppose you also want Universities to shut down their Astronomy programs – talk about something which has virtually no practical application!

Whether a skeptic researches Nessie, ghosts, alternative medicine, or who stole the cookie from the cookie jar, if it’s done in a rigorous and scientific manner, then it’s time well spent. Doubly so if the skeptic writes about it to share the lessons learned from the investigations like Ben Radford has done with his excellent book.

“…it is wrong always, everywhere, and for any one, to believe anything upon insufficient

evidence.” -William K. Clifford

It may be an ethical question, in that if we don’t avail ourselves with as much of the literature/evidence (of all “sides”) we may be guilty of being closed minded, and are unable to make informed decisions, because we lack the proper data. More to the point, it’s a bit unfair to require a person with an opposing view point to familiarize themselves with “The Evidence” aka our (read skeptics) P.O.V., if we haven’t familiarized ourselves (thoroughly) with their claims, that’s just hypocrisy.

I think Clifford’s point was, that if one allows sloppy thinking in one, seemingly trivial area, then it increases the chances of sloppy thinking, and poor reasoning to spread into other more important areas of our decision making processes. On the other hand, I have a really difficult time accepting that I am being unethical by not knowing the operating hours of Burger King.

I suppose “I don’t know?” is the most responsible, and ethical answer that we can muster, much of the time.

Coming from the Paranormal circles myself where to this very day, I still receive hate mail and death threats, I can honestly say, the majority of the Paranormal crowd won’t accept skepticism. Regardless of whether it’s delivered by a mild mannered, logical gentleman or a foul mouthed, baseball bat wielding maniac in a ski mask.

The end result will be a logical explanation built on a foundation of logic and a group of mouth breathing, Dorito stained finger idiots who will always use the safety net excuse “the paranormal can’t be explained.” Sad but true.

People still believe in orbs. Enough said.

I’m currently researching amateur pararnormal investigation groups (and my stack of books looked much like Daniel’s picture but my subjects were all over the spectrum). It does feel odd to pay attention to what many people think is silliness. However, there are well over 1000 of these groups in the US alone, 30 million people are in the TV audience of Ghost Hunters. That’s not small change. The paranormal is a HUGE part of our culture (and as long as there is science, there will be pseudoscience), so it is very meaningful to delve into it.

As part of my review on Radford’s books, which I also enjoyed immensely, I said that I hope he inspires more people to get out and do the research the right way. Perhaps more investigators will be willing to accept the non-pararnormal answer that is supported by evidence instead of feeding into the romantic paranormal realm.

Finally, it’s important to notice in these stories about paranormal seekers and experiencers that they are deeply affected by their beliefs. While many ghost hunters publicly state they really want to help people, Ben notes that he hopes he can help people sleep better at night too by understanding the mystery’s cause was of this world.

Can somebody out there who is aware of good quality sceptical research into fairly recent miracles claimed by religious authorities [e.g. apparitions of the Virgin Mary at Lourdes, Fatima; group apparition claimed for Knock , Ireland, etc], give access details please?

Well, I can think of few better places to start than with Joe Nickell. His book is perhaps a little further out of date than you would like, but it is excellent! (He has more recent articles in the Skeptical Inquirer, etc.) http://www.joenickell.com/MiracleClaimsInvest/miracleclaiminvest1.html

Researching ghosts and paranormal whatnot is fun, but it is also important in a general way, even if it can only accomplish so much. Mr. Randi’s book on Nostrodamus, for example, has been personally used by me to show someone who should have known better that it is a myth. He wouldn’t believe me, but when something is in print, people take it more seriously. But, Mr. Randi himself points out at the end of the book that many people will go on believing the silly things about Nostrodamus because it is more fun to believe them. All you can ever hope to persuade is a few people who have open minds. And, of course, as sceptics know, once in a while, strange things turn out to be true. Gorillas, Giant Pandas and many other animals were once thought of as legendary by Europeans, I believe until the early to mid-1800s when explorers came into contact with them. I can’t conceive that will happen with ghosts or demons, but it is at least conceivable to me that extraterrestials have visited earth (though I seriously doubt it). I was once sceptical of the Atkins diet, thought it abject nonsense that you could eat fattening foods and lose weight – I’ve been on it for about 15 years or so now – the only diet that has ever worked for me over time. I felt acupuncture was mystical hocus pocus, but tried it in desperation in the 1990s – it changed my life, relieving me of much chronic pain doctors couldn’t touch. So, do your research and have fun. I’m all for it.

Research on Atkins and acupuncture:

https://skepticblog.org/2009/12/14/still-on-that-low-carb-diet/

http://www.sciencebasedmedicine.org/?cat=8

I totally agree with Mr. Loxton that serious skeptical scholarship is justified and necessary but I need to add it is bound to be a special activity for the few dedicated skeptical workers inclined to do this tedious work. Equally important is the need to inform and popularise basic philosophical tenets of atheism/skepticism contained in such works as Lucretius’s ” De Rerum Natura ” such as ” Ex nihil nihilo ” or as even the pseudo-skeptic Sigmund Freud’s ” The Future of an illusion “. They provide quick knock-out punches that no theist has ever been able to refute.

Theism is apparently impervious to science,reason,and logic. The idea of a “knock-out punch” is only useful for those who are open to rational arguments. True believers will deny,dismiss,willfully misunderstand and ignore any evidence that doesn’t fit their world view. Critical thinkers should be wary of falling into the same trap.

I agree. Hard evidence to a magical thinker is like an unstoppable force vs an immovable object.

Just as there is no alternative medicine only medicine, much as there is no pseudoscience only science, perhaps there should be no skepticism only critical thinking and the scientific method. To the casual, uninvested observer a lot of the current skepticism appears to be simple debunking reflexively applied by know-it-all buzz kills (Cliff Clavin comes to mind). Framing the argument as the Skeptical Community _versus_ the paranormal, SCAM, UFO, cryptobiology, or religious communities reinforces this perception, not only among the magical thinkers, but also among the great majority of people who are merely disinterested.

I agree with Giles Corey. We need to find a way to really communicate with the general public in ways that don’t set us apart from them. We have to be careful how we label things and ourselves (e.g., “skeptic”) because terms come laden with meanings, often different to different people (e.g., “theory” – as used by much of the public vs. the specific definition assumed by most scientists).